In last month’s article we reviewed the anatomy and physiology of tendons. This month we will examine available treatment options for tendon disorders. After having started this article, I quickly realized that the content would exceed the allowable length for printed publication. As a result, the topic of tendon treatment will be split into a two-part series.

In last month’s article we reviewed the anatomy and physiology of tendons. This month we will examine available treatment options for tendon disorders. After having started this article, I quickly realized that the content would exceed the allowable length for printed publication. As a result, the topic of tendon treatment will be split into a two-part series.

Let’s get started with Part One…

Tendon treatment is remarkably complex; at least in this humble clinician’s opinion.

If was simple, it might involve the standard use of one type of pill, injection, exercise, etc. This is, however, far from clinical reality. Despite the marvelous advances in modern medicine, there is still much that we don’t know about tendons. What adds to the sense of complexity is an enormous number of variables to consider. A patient’s age, sex, height, weight, health status, nutrition, occupation, activity level, and movement patterns all effect treatment choices. Additionally, a tendon’s location, function, appearance, and other characteristics influence care considerations.

Diagnosing The Problem: Shooting At The Right Target

The first step in treating a tendon problem is making sure that you’re actually dealing with a tendon problem. Very often, pain and dysfunction that is thought to be related to a tendon is in fact caused by something else. A common example of this is when anterior knee pain is attributed to the patellar tendon but is instead caused by the patellofemoral joint – the region behind the kneecap. One way to help discern whether pain is related to a tendon is by using the single-finger test. Tendon pain is usually very focal in nature. This is particularly true of the energy storing tendons such as the Achilles and patellar tendons. If the pain location is more diffuse than can be indicated by a finger or two, other structures such as the tendon sheath, the surrounding fat pad, and the adjacent joint might be involved.

As an extension of the physical exam, various imaging studies can also provide valuable information about possible sources of pain. In my practice, I use an ultrasound machine to visualize tendons and other structures, which produces high-resolution images of the anatomy and offers the ability to study tissue while the patient engages in active movement. By using this imaging modality, I am able to identify discrete tendon problems that may otherwise elude proper diagnosis.

Another issue plaguing tendon treatment is the abundance of unfortunate misnomers in the medical terminology. The word “tendinitis”, for example, is very commonly used to describe tendon problems. The suffix “-itis” denotes inflammation. The issue with this is that most tendon problems have very little to do with inflammation.

But wait; didn’t I say something about inflammation in the first stage of tendon healing in the previous article? Yeah, I did. Here’s the deal. Acute inflammatory tendinopathies exist, particularly in the setting of acute rupture or laceration. The vast majority of tendon problems, however, tend to be related to chronic degenerative changes, even when pain seems to have had a fairly acute onset. Many histologic studies in which tendon tissue was examined under a microscope have demonstrated that evidence of inflammation is seldom present in the setting of tendon pain. Instead, such studies commonly reveal collage disarray, increased matrix protein, hypercellularity, and new growth of blood vessels – collectively, degenerative changes. This is an important distinction because inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions are treated quite differently.

Another example of the many misnomers – lateral epicondylitis a.k.a. tennis elbow. The name might suggest that this condition involves inflammation of the epicondyle – a bony portion of the elbow. And yet, lateral epicondylitis involves neither inflammation nor the bone. Instead, it is primarily caused by degeneration of one or more tendons (most often the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon – got that?). Oh, and on top that that, most of the people who get “tennis elbow” have never even played a single game of tennis.

Exercise: Work It Out

Exercise: Work It Out

Exercise is the foundation of tendon treatment. It has been repeatedly shown that tendon pain and dysfunction improve when the tendon is placed under load. This is quite contrary to the bygone belief that a painful tendon should be treated with rest. When there is an absence of tension, tendon tissue turns to mush. The tissue architecture begins to degrade, the mechanical strength of the tendon decreases, the kinetic chain becomes dysfunctional, and mind-muscle connection becomes impaired. On the other hand, when tension is applied to a tendon, a reorganization of the tendon structures occurs through a process known as mechanotransduction. The typical net result is less pain and a fortification of the tendon structure. How does it work? We’re not exactly sure. There is a lot going on here. When movement occurs and a load is introduced, those forces are turned into biochemical signals. Cells interact with one another by using various communication chemicals. There is also an upregulation of certain genes and increased production of various proteins. (Didn’t I tell you that it was complicated?) To expand on just a single part of the process, a group of proteins known as integrins function mechanically within cells to activate much of the cellular response to load. When tension is applied to a tendon, these proteins literally flip like a switch, which alters the cellular structure and initiates a cascade of downstream events.

While avoidance of excessive load is an appropriate measure in tendon rehabilitation, a structured program that allows for progressive increase in load and a graded return to normal activity has been shown to provide excellent clinical outcomes. Regarding which exercises to perform and which programs to follow, this is where quite a bit of fitness finesse comes into play, which is largely predicated on individual symptoms and the particular tendon involved with a given case. There are many rehabilitation exercise protocols that have been recommended for a variety of tendon disorders.

A great place to start might be with the implementation of isometric resistance exercise. This is a type of strength training in which the joint angle and muscle length do not change during contraction. In other words, it’s squeezing a muscle (and the associated tendon) without moving. Performing this type of exercise during which you might hold the squeeze for up to 45 seconds has been shown to significantly reduce pain and increase strength in the setting of a tendinopathy. I would recommend the use of machines for this type of rehabilitation. In the case of an Achilles tendon problem, an example of an isometric rehab protocol might be performing a seated calf raise while holding the weight at mid-range for 45 seconds x 4 repetitions, resting for 1-2 minutes between reps. This could be performed 2-3 times per day.

After having graduated from isometrics, one might begin to incorporate isotonic exercises by slowing moving weight up and down. In the case of the calf raises, 4 sets of 6-8 slow and heavy reps would be appropriate.

In recent years, there has been a lot of interest in programs that emphasize the eccentric (negative) portion of movements. Given some of the research results, it may be worth focusing on committing extra effort to the action of slowly lowering the weight during an exercise.

Beyond this point, assuming that symptoms are better controlled, more functional and sport-specific activities may be integrated into the rehab program.

Nutrition: You Are What You Eat

How can I make my comments on the importance of nutrition somewhat interesting? We’ve been told to eat our veggies and limit the junk food since we children. It’s nothing new and frankly, it’s quite boring. Nevertheless, I feel compelled to emphasize the massive impact that nutrition has on how you feel and function. I find that it’s the type of thing that you almost have to experience before you believe it. In the words of Levar Burton, “You don’t have to take my word for it.” And while you don’t have to take my word for it, a personal story may help to underscore this notion.

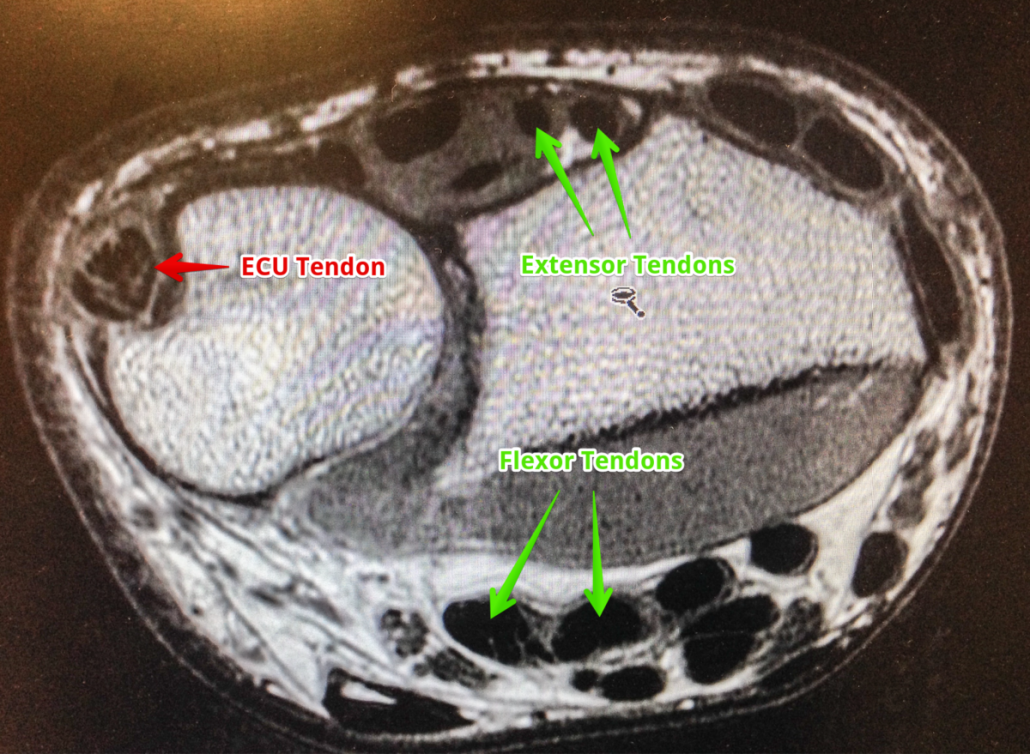

Over the years I’ve managed to experience my fair share of musculoskeletal injuries. Among them is ECU tendinosis – degeneration of the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon near the wrist. I think that this was largely related to frequent straight barbell curls, which is not a great movement for my particular structure. (Curls using a cambered bar are much better for me, as I think they are for most.) Four years ago I was preparing for a physique contest, which involved adherence to a rather strict diet. During that time, I felt simply fantastic and prior injuries, including the ECU tendinosis, were causing zero discomfort despite regular, intense training sessions. Following the competition, I began to eat a more liberal diet and within approximately 1 week, I felt crippled. I could not rotate my wrist to open a doorknob or turn the steering wheel of my car because the ECU tendons were so painful. Nothing other than my diet had changed. Since that time, through dietary vigilance, I have noted an even more direct connection between how I feel and function and what I am eating.

There are many things to consider on a macro and micro scale when relating nutritional constituents to the health of tendons. Whole foods deserve the most attention as they often contain optimal combinations of nutrients, many of which act synergistically to maximize tissue health. While we know that zinc, vitamin C, vitamin E, manganese, and many other compounds are tremendously important for collagen synthesis and strength, this may appear on your plate as peppers, kale, beef, beans, or broccoli. While various nutritional supplements and dietary constituents will be discussed in the next section, the focus on whole foods cannot be overemphasized.

Next month, in Part Two of this series, we will explore the utility of medications, nutritional supplements, platelet-rich plasma, stem cell therapy, therapeutic peptides, and a number of other available tendon treatments.