When people present to my medical clinic and begin to describe their “symptoms”, I often hear some version of the following:

When people present to my medical clinic and begin to describe their “symptoms”, I often hear some version of the following:

“I have a bone spur.”

“I have bulging discs.”

“I have a labral tear.”

These statements, however, describe radiologic findings rather than symptoms.

While bone spurs, bulging discs, and labral tears can be involved in a painful process, patients are often surprised to learn that pain need not necessarily be associated with these findings and that radiologic abnormalities may even serve to distract from the actual causes of pain.

Take for example the notorious bone spur. The effects of a bone spur on nearby structures such as nerves may lead to discomfort in some, but the spur itself is not painful. It forms in response to local inflammation and abnormal patterns of loading and thus represents normal adaptation to a preceding process. (For more on the concept of adaption, refer to the November 2018 article titled Our Crazy Bodies, Our Crazy Bones.)

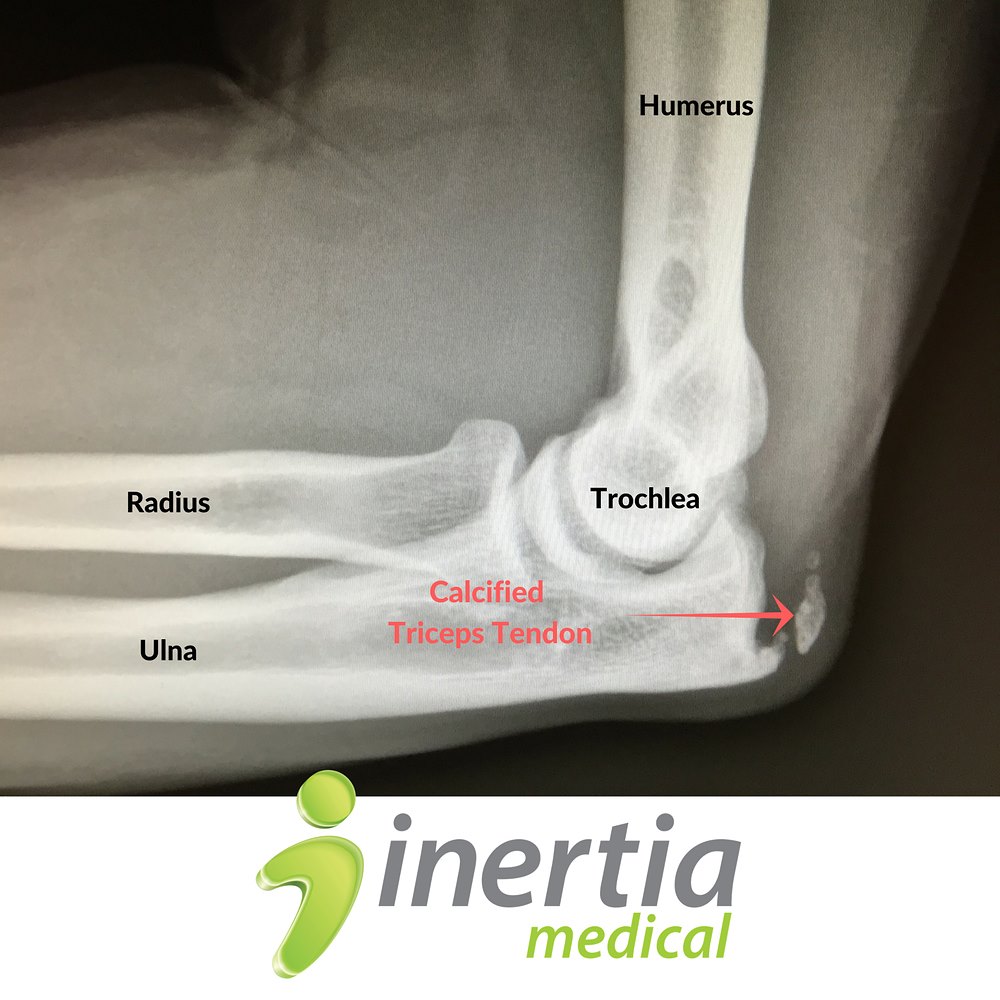

An analogous condition called calcific tendinopathy involves the deposition of calcium within tendon tissue, which is also very often the result of inflammation and abnormal loading. I describe this to patients by saying that the calcium can be thought of as spackling that our bodies lay down within the tendon in an attempt to fortify and repair the tendon structure. As with bone spurs, many of these cases are best treated by addressing the underlying problems that led to calcification in the first place.

In addition to the point that “abnormal” imaging findings need not necessarily cause pain, it is important to recognize that such findings are also quite common. I can remember discussing related topics with a shoulder surgeon who said that when a teenage baseball player is found to have a shoulder labrum tear, he would often congratulate them and say, “You now have the shoulder of a major league baseball player” since labral tears are so frequently found in MLB players.

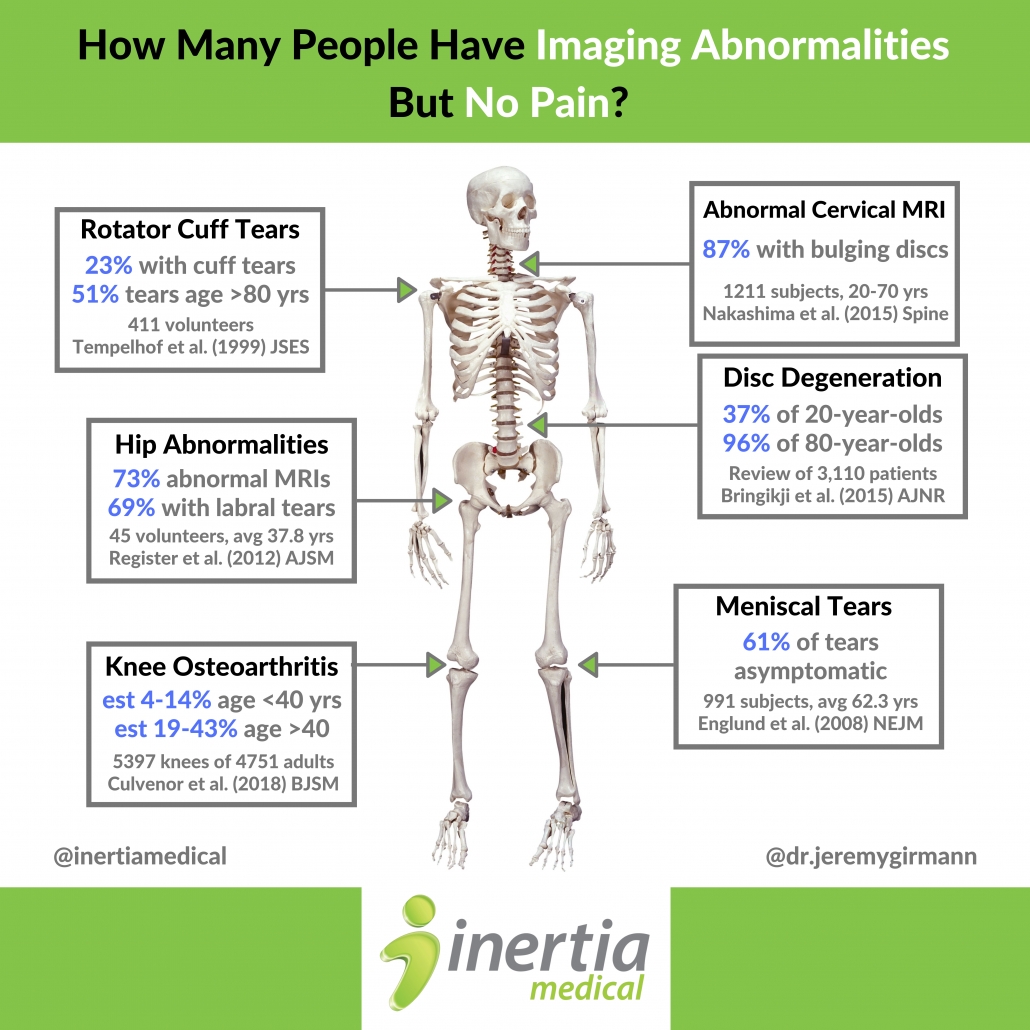

A number of studies have looked at the prevalence of abnormal imaging findings in asymptomatic individuals. In 1999, an article in the Journal of Elbow and Shoulder Surgery reported that 23% of 411 asymptomatic volunteers were found to have rotator cuff tears. In 2008, Englund et al. found that 61% of people with meniscal tears on MRI reported no symptoms. In 2012, an article in the American Journal of Sports Medicine revealed that 69% of asymptomatic patients were found to have hip labrum tears. Also, in a review of 3,110 patients, Bringikji et al. found that 37% of 20-year-olds and 96% of 80-year-olds had radiologic evidence of degenerative disc disease.

That leads me to another point. Degenerative is a lousy term. Many patients hear about their “degenerative disc disease” and immediately surrender to a vision of inexorable bodily decay that will lead to certain pain and despair. As a result, “age-related changes” has been suggested as a replacement term. Just as our skin wrinkles over time, so too will the rest of our bodies change. This is a normal part of aging. We do not look at someone with wrinkles around their eyes and insist that they have degenerative face disease.

A few years ago, it would pain me to hear a medical provider across the hall describe every single subtle anatomic change that they could identify on spinal imaging studies while visiting with patients. Without the simultaneous explanation that many of these findings are exceptionally common and may not be problematic, the patients would inevitably leave with the self-summarized notion that “my back is really jacked up.” As providers, we need to emphasize patient education but we must also consider the clinical context. Allowing patients to strongly identify with a particular diagnosis such as “degenerative disc disease” can be not only misleading, but may also cause them to take ownership of the diagnosis more than the requisite active participation in their treatment plan.

A few years ago, it would pain me to hear a medical provider across the hall describe every single subtle anatomic change that they could identify on spinal imaging studies while visiting with patients. Without the simultaneous explanation that many of these findings are exceptionally common and may not be problematic, the patients would inevitably leave with the self-summarized notion that “my back is really jacked up.” As providers, we need to emphasize patient education but we must also consider the clinical context. Allowing patients to strongly identify with a particular diagnosis such as “degenerative disc disease” can be not only misleading, but may also cause them to take ownership of the diagnosis more than the requisite active participation in their treatment plan.

Ultimately, the point here is that providers need to treat the patient, not the image. Likewise, patients need not perseverate on imaging abnormalities but should focus rather on the available treatments for their specific symptoms.